Introduction to the Great Migrations

THE FIRST GREAT MIGRATION 1916-1930

Background: Richard Allen and AME Denomination

Philadelphia Origins: In 1786, Black worshippers left St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church to form their own mutual aid association, called the Free African Society. With Richard Allen’s leadership, they quickly transformed their association into a congregation, and embarked on a journey to start the first Black denomination. Through the Pennsylvania courts, Allen secured the right for his congregation to exist independent of the Methodist Church. As other Black churches sought religious autonomy and freedom from racism, the AME Church spread throughout the Northeast and Midwest. After the Civil War, AME membership below the Mason-Dixon Line began to outnumber the rest of the country, reaching 400,000 in 1880. Advancing a strong liberation theology, African Methodism crossed the Atlantic into Liberia and Sierra Leone in 1891, and into South Africa in 1896.

Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal denomination, was born of slave parents in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on February 14, 1760. The Allen Family was owned by Benjamin Chew, who served as attorney-general and Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania High Court of Errors and Appeals. Allen was influenced by Methodist preachers operating in the area and with the permission of his master, joined the Methodist Society. Allen’s preaching was so powerful that he converted his owner and asked him to outline how he could purchase his freedom. Working as a day laborer, brick master and teamster, Allen purchased freedom for himself and one of his brothers. As a free man, Allen moved back to Philadelphia where, in 1786, he and Absalom Jones began to conduct prayer meetings for fellow Africans. Although they continued to worship at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, Allen proposed that the African members build a separate house of worship. His foresight was confirmed one Sunday morning in November 1786. As Absalom Jones, William White and Richard Allen knelt in prayer at the front of the church, the men were pulled from their knees and ordered to the rear by St. George’s officials. In protest of their ill treatment and escalating measures of segregation within the church, the African members walked out of St. George’s Methodist Church.

The following spring, Allen and Jones formalized the association composed of their flock of worshippers from St. George’s. On April 12, 1787, the Free African Society was born, the first organization of its kind established in the United States. With Mother Bethel AME Church at the helm, the African Methodist Episcopal denomination was organized in Philadelphia on April 9, 1816, proclaiming a mission of liberation for African Americans.

The Southern Experience

News of the AME mission spread to the South, spawning new congregations such as the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. The beginnings of Emanuel AME strongly mirrored those of Mother Bethel in Philadelphia. In 1816, Black members of the Charleston Methodist Episcopal Church withdrew membership over disputed burial grounds. Rev. Morris Brown led the group to organize a church for persons of color and sought to have it affiliated with Allen's church. In 1822 Emanuel AME was investigated for its involvement with a planned slave revolt. Denmark Vesey, one of the founders, organized a major slave uprising in Charleston. The plot created mass hysteria throughout the Carolinas and the South. Brown, suspected but never convicted of knowledge of the plot, went north to Philadelphia, where he eventually became the second bishop of the AME denomination.

In the late 1800s, African Americans living under oppressive Jim Crow laws in the South faced great challenges. Laws in South Carolina were particularly harsh, as whites sought to control the large African American population. “Because black politicians in the Reconstruction Era had been rather successful in legislating public equality measures, the Conservatives’ first target was South Carolina’s African Americans, who still comprised 60 percent of the total population” (Townsend, 2009, p. 204). As a result of these concerted efforts to dismantle the political access African Americans had gained, they were systematically disenfranchised, making life progressively more unbearable. In Philadelphia, however, well-established and vital African American communities had formed by the end of the 19th century, providing formal and informal networks to resources and services (DuBois, 1899).

Word of a better life in the North soon spread amongst the Southern African American population, resulting in the first wave of the Great Migration. The relationship between Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia and Emanuel AME Church in Charleston became the vehicle for moving thousands of African Americans from South Carolina to Philadelphia. This proved to be a mixed blessing, however, as the AME church “saw its southern heartland depopulated. In South Carolina alone, more than 100 AME congregations were abandoned in the years between 1916 and 1926. In all, the church lost nearly half its southern adherents to migration” (Reich, 2014, p.3).

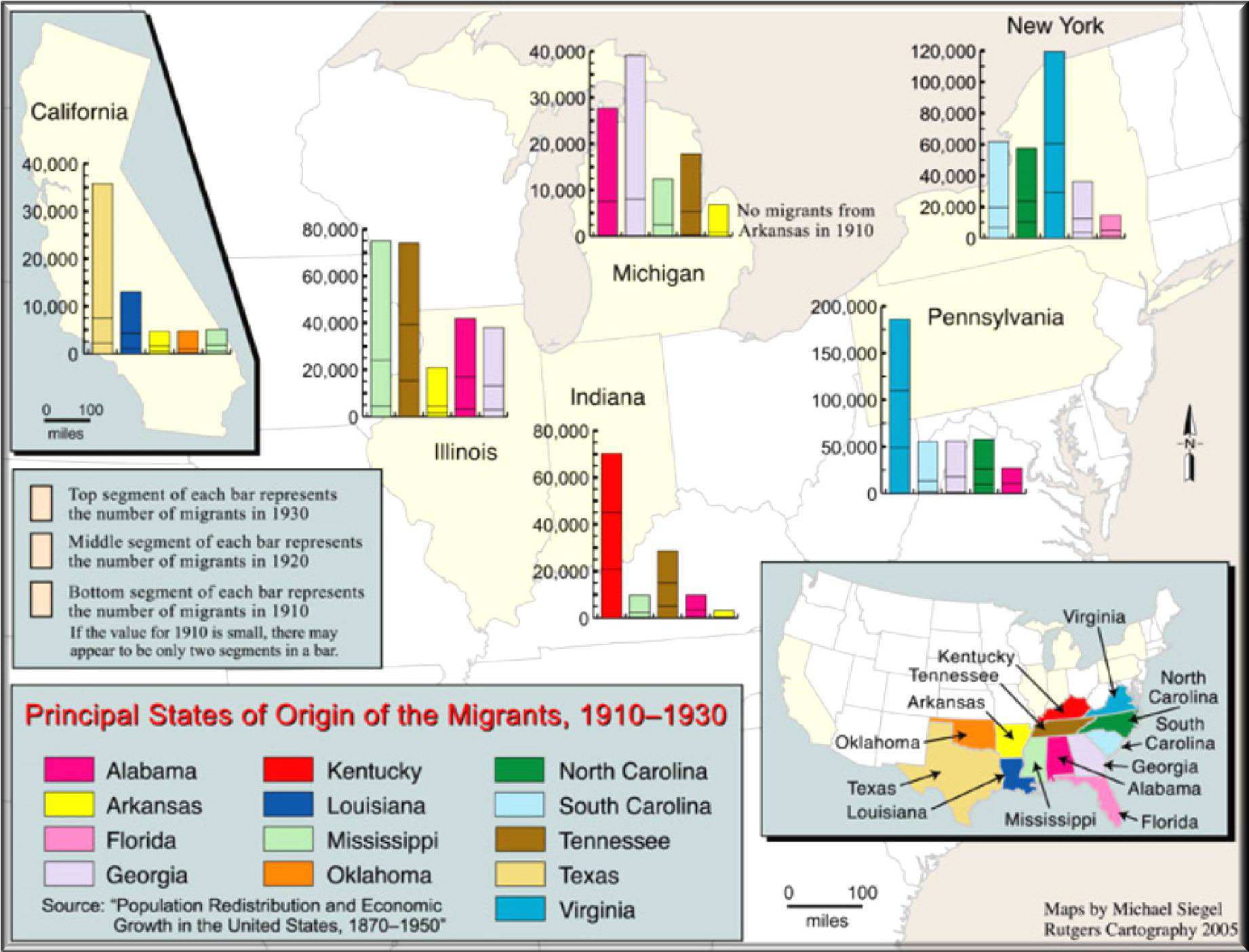

Scholars estimate that as many as 400,000 African Americans fled the South between 1916 and 1918 (Berlin, 2010; Mark, 1989). By 1924, Philadelphia had the nation’s second largest urban African American population (Miller, 1984), tripling from 84,000 to nearly 220,000, between 1910 and 1930 (Finkelman, 2009). The AME denomination became a hub for social connections during this period, as AME congregations emerged throughout the Delaware Valley. “If you came to Mother Bethel and wanted to move out to Chester, Mother Bethel would send you to another AME church, so you were in the same connection. It’s like the Underground Railroad, when you got here it didn’t mean you were staying, through some process the Church would get you connected” (Wilson, 2014).